Meet Tom, Christ Church's famous clock. He chimes 101 times at 9 o'clock (Oxford Time) each night. This was the time of the centuries-long curfew, designed to separate the students from the townspeople and prevent Town and Gown riots. It should be noted that Oxford Time is five minutes after London time as we are 1 degree west of the Greenwich Meridian. Legally, Oxford Time no longer exists, since with the advent of the railways it just became too complicated to have different times in every town and railway time (London time) was eventually applied to the entire country. However, Oxford (and Christ Church in particular) is reluctant to shed its traditions, so Christ Church preserves Oxford Time in the 5 minutes extra it claims before the tolling of Great Tom.

0 Comments

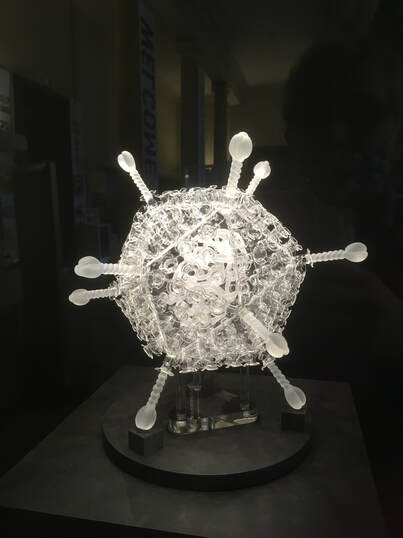

This is Luke Jerram's fabulous Oxford Astra-Zeneca Nanoparticle. It is enlarged 1 million times and was made to commemorate the 10 millionth UK Covid jab. He made 6, sold 5 and made £17.5k for Médecins sans Frontières. Come and visit it at the Oxford Museum of the History of Science! (Booking required, closed Mondays) This is an article published in the now defunct Oxford Today on 12th February 2014 at the time of the Sochi Olympics. The online link has been removed and I thought it a pity to let it go to waste. I shall post the second installment shortly.

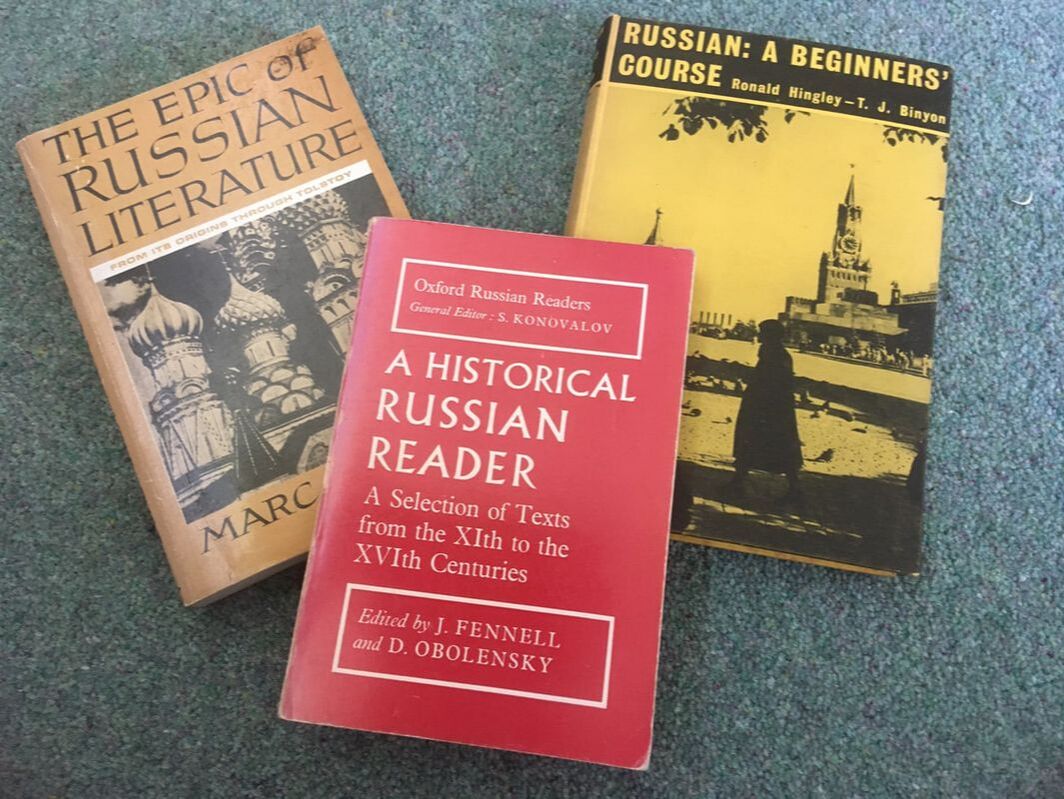

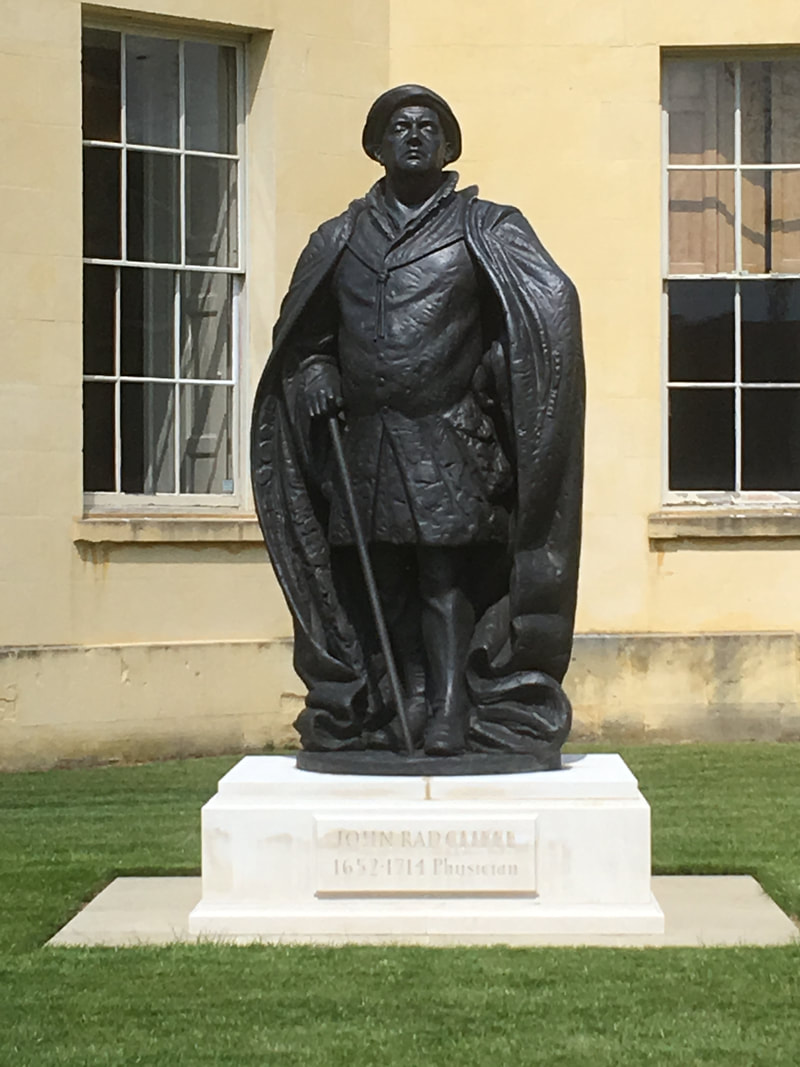

12 February 2014 Oxford Today Oxford’s Early Russian Connections By Victoria Bentata The first of a two-part series studying the city’s ties with the current Olympic hosts. While the Olympics is in full flow at Sochi, physical exertion has not often figured highly in Oxford’s contacts with Russia — though ‘good sport’ has undoubtedly been had by several high profile visitors, and the study of Russian is today enjoying one of its most successful periods ever. Oxford University’s first serious engagement with Russian was in 1696, when philologist Edward Bernard persuaded the Oxford University Press to buy a Cyrillic font from a Dutch printer in order to publish a Russian Grammar written in Latin by a German called Ludolf. Bernard thought it would be ‘a useful booke to our Russian merchants’. This was the first ever printed grammar of Russian and guaranteed Oxford a place in the history of Slavonic studies. Its publication presaged an unusual visit a couple of years later, in April 1698, by ‘a very uncouth fellow’ dressed in an enormous, scruffy black wig and a black kaftan with gold buttons, whose dirty hands were ‘scratched as though from scabies’. Tsar Peter the Great, taking time out from his study of shipbuilding on the London docks, arrived incognito and stayed in the Golden Cross Inn, where he clearly enjoyed a good evening — helped along by a couple of bottles of brandy and four bottles of sack wine. When he visited the Ashmolean the next morning (for all of fifteen minutes), the innkeeper accompanied him in his carriage. Heading across the road to Trinity College chapel, he realised that he had been recognised and that people were flocking to follow him. Irritated by the crowd, he simply turned tail and headed back to London. Later Russian visitors stayed slightly longer. Five young men arrived to study in Oxford in 1766. Unfortunately, two left with medical problems apparently occasioned by too much reading — no, really — and three ended up in the debtors’ jail. Nikitin, the man supposedly supervising their stay, was taken to court by the warden of Merton. Eventually, the Russian government took charge of the situation and repaid the students’ debts, while Nikitin, together with Suvorov, one of the students, was eventually admitted as an MA and wrote a book on trigonometry. In 1803 Suvorov published one of the first English Language Training books, designed to teach Russians English in 30 lessons. Diplomatic overtures were made during the late 18th century when the first Russian received an Honorary Doctorate from the University. He was Russia’s Minister to the Court of St James, Count Alexander Romanovich Vorontsov, who was apparently no more than 22 years old at the time, but did go on to have a creditable career as Russia’s Chancellor and Minister of Foreign Affairs. The most impressive Russian visit came in 1814, though, when Tsar Alexander I was invited to the University for a premature celebration of Napoleon’s downfall (together with the Prince Regent and the King of Prussia) and was awarded an Honorary Doctorate of Civil Law (DCL). The Allied Sovereigns attended a magnificent banquet for 200 at the Radcliffe Library and a ‘cold collation’ in the Codrington Library. Although accommodated in more regal style than his illustrious predecessor — in the Queen’s Room in Merton — it is recorded that the Tsar slept on a mattress on the floor, whilst his sister Ekaterina Pavlovna occupied the bed. Edward Nares, then Regius professor of Modern History, further records that the Tsar’s four servants ‘slept in their clothes on the landing place of the staircase, and did no small damage, by their foreign habits, and disregard of the value of the furniture’. This clearly didn’t upset the Warden, however, who was so excited that he personally paid for two stained-glass imperial eagles to be installed in the bedroom windows, which grace it to this day. Alexander, too, evidently enjoyed his stay and such was his largesse that his gifts are still amongst the finest treasures of both Merton and Magdalen Colleges. Merton Chapel is home to an enormous green vase made of Siberian jasper with a complimentary inscription to ‘Merton College, its warden and fellows, most enlightened and venerable men, as a token of pleasant memory of the hospitality accorded during his visit to Oxford’. Magdalen’s President, Martin Routh, meanwhile, received a magnificent silver salver imprinted with the imperial double-headed eagle (above). A portrait of the Tsar, requested by the University, still adorns the Examination Schools. Honorary DCLs were also conferred on the future Tsars Nicholas I in 1817 and Alexander II in 1839. However, possibly more deserving recipients were Ivan Turgenev, author of Fathers and Sons (and the first novelist ever to be awarded an Oxford honorary degree), and chemist Dmitri Mendeleev. © Victoria Bentata

Yesterday was Wednesday of 9th Week of Trinity Term when the University of Oxford traditionally celebrates its 'Festival of dedication' and awards honorary degrees to the great and the good. All participants are first invited to Lord Crewe's Benefaction - peaches, strawberries and champagne. They certainly looked very merry as they made their way towards the Sheldonian for the ceremony. The man with the page boy is Chris Patten, (Lord Patten of Barnes) Chancellor of Oxford University and last Governor of Hong Kong (and one time head of the BBC), the woman with the highly decorated gown behind him is Louise Richardson, first female Vice-Chancellor of the University of Oxford and expert on global terrorism. The very happy man in the red and cream gown is Yo Yo Ma, world famous Chinese-America celllist and one of this year's 'honorands'. The verger and the bedels lead the procession (final photo). For more information about Encaenia, go to the University's website at: http://www.ox.ac.uk/news-and-events/The-University-Year/Encaenia

I attended a private view of the Jeff Koons Exhibition at the Ashmolean last Friday. After coffee and croissants, Xa Sturgis, the museum's director, told us the story of how the Exhibition came to be: An Oxford University student society named after Edgar Wind, first Professor of Art at Oxford (see https://edgarwindsociety.co.uk/) decided to inaugurate a prize and present it to Jeff Koons. Koons was evidently thrilled and flew straight over from the States to receive his prize. He was slightly surprised to be greeted by 35 students in the basement of the Ashmolean, but was sufficiently impressed by the museum to subsequently agree to work with them to stage this exhibition. If you like steel representations of balloon animals and blue meditation balls in unusual settings, then this is definitely the exhibition for you. This is one of the last college barges still in existence. Many date from the 19th century. Members of colleges would use the barges as changing rooms and common rooms and watch the Torpids and Summer Eights rowing races on the Isis (the local name for the Thames) from these barges. One of them was sold in 2014 - asking price £150,000. This one is hidden near Donnington Bridge.

This is a Harris Hawk, regularly employed by some of the Oxford University colleges (and Oxford Castle) to discourage nesting pigeons. He comes out once a week and his job is to fly around looking hawkish....

No, not Xmas or Hanukah, but……….. ‘Interview Time’. Just as they come to the end of an exhausting term, which began with the induction of the ‘freshers’ in October, the academic staff of the colleges of the University of Oxford are gearing up again to choose next year’s intake. No ‘eight week term’ for them, nor for all the college and university staff - the administrators, who organise this mammoth logistical undertaking, the porters, the catering teams and the scouts who have to clean the rooms.

Just to put it into perspective, last year the colleges of the University of Oxford received over 20,000 applications. All of these applicants needed top scores (or predicted scores) in their A’level or equivalent exams just to attempt the selection process. Next, in most cases, they needed to do a written test, taking the form of an aptitude test for those subjects which they had never studied before. Such is the University’s eagerness to leave no stone unturned and no prospective Einstein undiscovered, that 10,000 of these applicants were invited to come and stay at a college and be interviewed. Moreover, they weren’t just interviewed once, but twice (at different colleges) and, in some cases, three times. And all for just 3,200 undergraduate places! The legendary Oxford Interview is really designed to give the applicant a taste of the Oxford Tutorial, the traditional hour a week which most Oxford students spend in close conversation with their Tutor. Once at the University, they have to come to tutorials equipped with an essay or problem sheet that they have spent the previous week researching and writing. For the interview, no essay, but a daunting leap into the unknown when they can be asked anything related to the subject they want to study. To make the process a little less terrifying and to find out more about Interviews at Oxford, go to the University of Oxford’s website at https://www.ox.ac.uk/admissions/undergraduate/applying-to-oxford/interviews?wssl=1 . This will give you a real taste of what to expect as an interviewee. It also gives some interesting insights into what the Tutors are looking for and contains some advice from former (successful) interviewees.  Anyone who has rowed in the University bumps races on the Isis will know that each race starts at Iffley Lock, beside a bronze cast of a Bull’s head with a ring in its nose. This ‘Starting Ring’ was presented by Lord Desborough in 1924. William Henry Grenfell, the first and last Lord Desborough, was one of the University of Oxford’s finest sportsmen. Six feet five inches tall, he was a man of extraordinary, restless energy who relished a challenge. In fact everything about the man and his life seems to have been on a grand scale and the sheer number and variety of his physical achievements is quite amazing: a Balliol man who captained the Oxford University Boat Club and rowed twice in the Boat Race, he apparently stroked an eight across the English Channel in 4 hours 22 minutes, twice swam across the rapids at the base of the Niagara Falls and climbed four Swiss mountains including the Matterhorn in eight days. He was also a wrestler, tennis player, three-time Amateur Punting Champion of the Upper Thames and in 1906, at the age of 50, won an Athens Olympics silver medal for fencing. His working life in politics as a Liberal MP was similarly varied and at one point he was rumoured to be serving on 115 committees simultaneously! However, his crowning achievement was surely to bring the Olympic Games to London. For Lord Desborough was a visionary and when he became the first President of the British Olympic Association at its creation in 1905, he worked tirelessly to promote and encourage excellence in sport. Never one to miss an opportunity, and noting the likely effect of the recent eruption of Vesuvius on the ability of the Italians to host the 1908 Olympics, he came to the rescue and persuaded his friend Baron de Coubertin, the founder of the modern Olympic movement, that England was ready and willing. The 1908 Games were thus organised in a mere eighteen months and Lord Desborough apparently gave a superlative total of 139 speeches at luncheons and functions to promote them. In fact he raised so much money that the public had to be asked not to send any more! Fittingly, he had the honour of firing the starting gun for the first ever marathon over 26 miles, with the finishing line at the feet of King Edward VII. Following the success of the London Olympics, Lord Desborough wrote in 1910, 'In the Games in London were assembled some two thousand young men…representative of the generation into whose hands the destinies of most of the nations of the world are passing at this moment…and we hope that their meeting…may have a beneficial effect hereafter on the cause of international peace.' Tragically for the nation and for Baron Desborough of Taplow himself, international peace was not to be, at least in the short term, and he lost two of his three sons to the First World War with his third and youngest son dying in a car accident in 1926. Despite the Times mistakenly publishing his obituary in 1920, occasioning a memorable Pathé newsreel title "Lord Desborough - erroneously reported dead a few days ago - unveils War Memorial", Lord Desborough lived until 1945 and died at the age of 90. His dedication to sport and to Oxford never waned and despite the desperate sadness of his family story, he continued to be active in sport, becoming president of the Amateur Athletic Association (also, incidentally, founded in Oxford - in the bar of the Randolph Hotel) from 1930 to 1936. His 1913 book Fifty Years of Sport at Oxford, Cambridge and the Great Public Schools is now a collector’s item, but his vision for the future of sport in this country is alive and well and the inspiration for the most recent London Olympic Games. Having discovered Lord Desborough, purely by reading the inscription on the starting ring at Iffley Lock and investigating further, I recently discovered his wife, who seems to have been entirely as extraordinary, gifted, energetic and life-enhancing as her husband. Richard Davenport-Hines has written a lovely biography of this great lady, 'whose whole existence seemed a cry for life but was dogged by death' and which also stands as a memorial to her sons, of which The Balliol War Memorial Book apparently says ‘Both were intensely alive: both were the joy of their friends’. The book is called Ettie: The Intimate Life and Dauntless Spirit of Lady Desborough. |

AuthorI am fascinated by the history of Oxford and am constantly learning new things. I'd like to share some of them with you. Archives

February 2023

CategoriesMy favourite websites:

Neats Home Garden John Garth Tolkien's Oxford |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed